"https://twitter.com/phildini/status/580879418337316864"

At 18F, our projects are open source from the beginning and nothing makes us happier than getting contributions from the public.That’s why we published a contributor’s guide to our code.

With the National Day of Civic Hacking fast approaching, we’ve been thinking about how to make our projects as accessible as possible for anyone who would like to adapt them or help us improve them.

We’re passing along the ideas we’ve batted around, with the hopes that it will inspire you to help out with one of our projects for the National Day of Civic Hacking on June 6. We’re also really interested in throwing these ideas to the wider community for thoughts and feedback on how to further improve them. Please leave a comment on this GitHub issue to share any ideas you have.

The National Day of Civic Hacking is a great time to attend — or host — your first hackathon. Below, we’ve outlined some strategies for first-time hackathon hosts. These tips will help participants feel welcome, and help them maximize their contributions.

Explicitly welcome newcomers with a new contributor guide

Usability testers, accessibility experts, researchers, data cleaners, writers, translators, subject-matter experts, and content designers are all people who can (and want to) help projects, provided they know how to navigate a hackathon and access projects ready for their input. GitHub repository pages are very busy; it’s not enough to link to them in the meeting materials and assume that everyone will be able to find the Issues tab. Newcomers also may not understand how to make a branch or file an accompanying pull request (or even what “pull request” means).

You can help in a few different ways:

- Create an online guide for newcomers that’s part of the hackathon’s organizing materials, and make sure it’s part of the official hackathon materials bundle.

- Designate a physical location at the hackathon where people can gather for help (an Info Booth, of sorts), and make sure the location is clearly labeled

- Elect a designated person (or a few people) to act as a welcoming committee for newcomers. It can be difficult for organizers to play this role with so much going on, so you definitely want to identify people who can help newcomers. Ideally, you will have some experienced hackers on-hand who are willing to take on this role. If not, review your RSVP list a week or two before the event and ask a few newcomers if they’d like to join the welcome committee. One week before the event, invite these participants to a prep night and have them test the install instructions and improve the welcome materials. Not only will you have a formalized welcome committee, but the new participants will feel welcomed.

Organizational efforts like these ensure that people spend time hacking with their best skills. For example, Wikimedia hackathons have an explicit buddy-pairing system.

Clearly define projects and enumerate ways newcomers can get involved with each

Last month, we co-hosted GovTechHack, a San-Francisco-based hackathon where civic-minded coders, builders, designers, and other creative folks came together to work on open source and open data projects. Before the event began, we wrote out documentation for each project, which included:

- The project’s name

- The project’s live URL, if it existed

- The project’s source code repository

- The project’s purpose and impact

- Concrete, clearly defined ways contributors could contribute during the hackathon

- The project ambassadors: people who could help answer questions during or after the hackathon

You can see an example of one of these projects here. Though this project documentation helped enormously, we’d make a few changes the next time around. We wish we’d also:

- Sent participants this information before the event, along with a detailed guide to software/libraries/gems to install for each project, so participants knew what to expect and how to prep their computers to participate. (Many hackathons end up with folks spending the first half of their day setting up local dev environment. The more you can do ahead of time to alleviate this, the more time people will have to hack!)

- Included this information on the GitHub page directly, perhaps in the README.md file, which people see when they’re checking out any of our projects. (Example: our site’s README.md)

- Included a checklist for users (like this one)

- Added a section on how non-coders could have helped each project. It’s worth thinking about and then articulating — in writing — how people with other areas of expertise or knowledge can help during a hackday. If you don’t have time to write these issues out, you can open an issue that asks for someone to interview you about them. Voila! Problem solved.

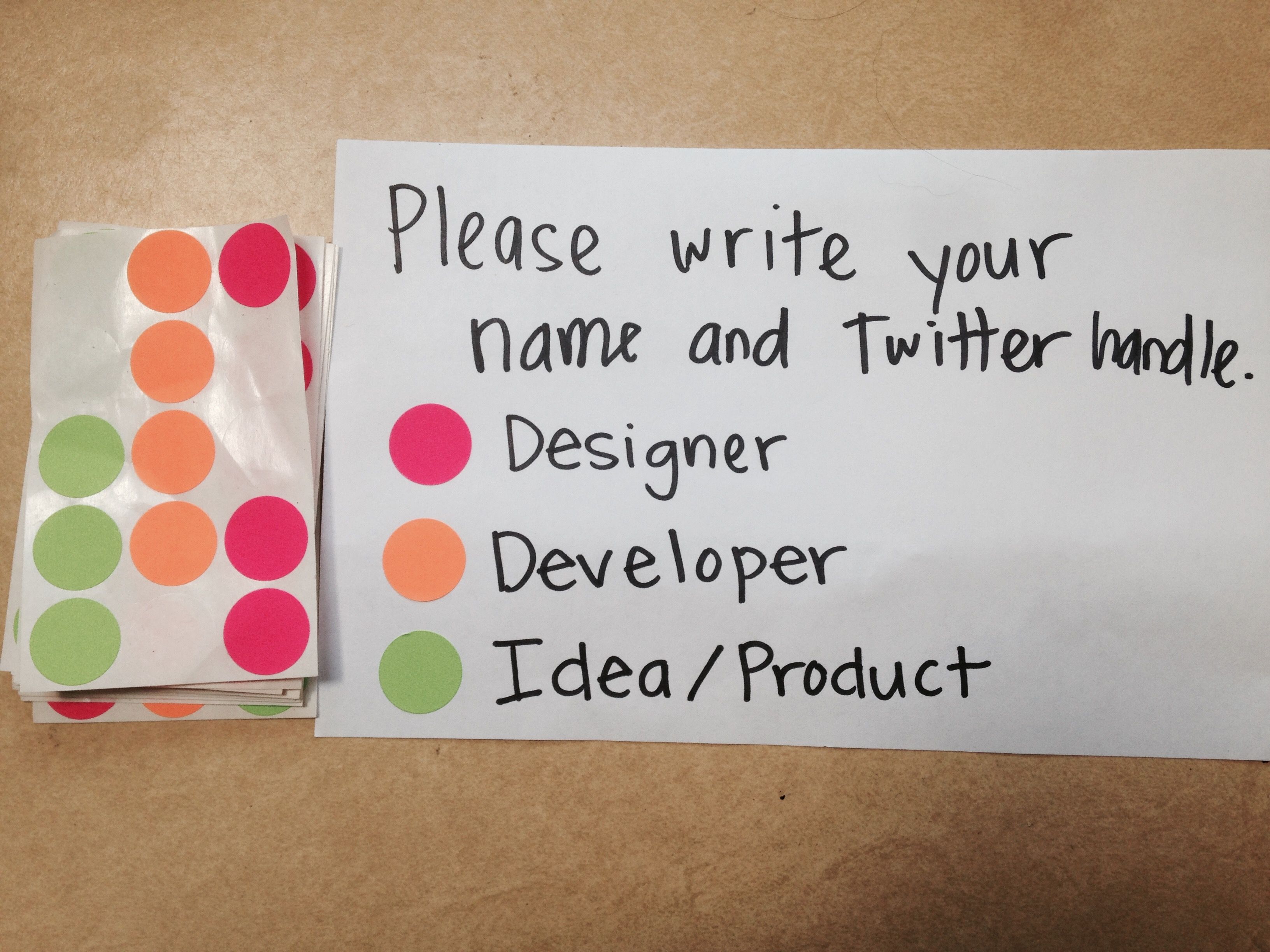

Make really good nametags for people

Sarah Allen, a developer at 18F, passes along nametags, pictured below, which were used at the GovTechHack. The nametags used color-coded stickers to delineate the skills people had at the Hackathon. Nametags can also be used to list Twitter handles, preferred gender pronouns, and skills or interests people have. Listing interests on a nametag also helps facilitate conversations between people who may be meeting for the first time.

Clearly label issues on GitHub with ways people can help

It is always a good idea to label GitHub issues that could use outside hands — we use the “Help Wanted” label. Government open source projects with this label are listed on GovCode, and civic tech projects with the same label are listed on the Civic Tech Issue Finder, which allow developers to jump in immediately.

Other tags make it particularly easy for new civic hackers to jump right in and get started. Our colleague, Julia Elman, pointed us to these GitHub labels that categorize beginner-friendly issues. Using the Beginner Friendly tag allows anyone who is new to the space immediately see where they can help. Feel free to grab these labels or create labels for your own projects. (18F’s Aidan Feldman has created a list of labels you can use for new projects.)

Make your team available for people who hack remotely

Not everyone can get to a nearby city to hack on the National Civic Day of Hacking, but this doesn’t mean they should be excluded from participating. During our GovTechHack, members of the 18F team – maintainers of the projects, especially – were available for questions and consultations, even if participants weren’t physically in San Francisco. You can connect with people in many ways, including chat rooms, video chats, social media such as Twitter or Facebook groups, or listservs. (These also help establish a larger community around the open source project. For example, the 18F project Midas has a Google group where community members can talk with our developer team.)

Online chat spaces allow participants to interact with one another beyond the physical space where the hackathon is taking place. Using a chat program during an event helps remote participants feel more connected to the in-person event, and also allows all members of the team to more easily converse in real-time. This also gives participants a space to connect with each other beyond the event, if they choose to do so.

Personally invite contributions

A personal invitation might be all it takes to turn a project user into a project contributor. If someone opens an issue that’s easily solved, think about offering to walk that person through the process of submitting a pull request. If a hackathon team dreams up a great new feature, work with them to implement it. Events like the National Day of Civic Hacking are opportunities to show people that their contributions are being received by real people who are delighted to have them contribute.

Develop a toolkit for participants

Our colleagues at GSA have created a toolkit to help people get started on open data projects. You can fork the toolkit or develop your own. GitHub also publishes a guide that teaches people how to do various tasks, such as Fork a Repo or Add SSH keys. And lastly, feel free to share our detailed tutorial, How to Use the Terminal and GitHub, for anyone new to this space.

You may also want to look at our checklist for open source projects, our maintainer guidelines for open source projects, and a hackathon guide 18F’s Leah Bannon recently wrote.

If you have thoughts or feedback on how to improve this guide, please leave a comment on this GitHub issue to share any ideas you have or have seen from other hackathons. If you’d like to contribute to an 18F project during National Day of Civic Hacking (or in general), check out our issues on GovCode.